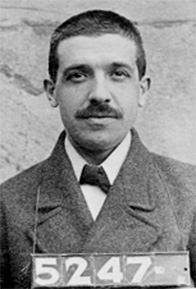

Charles Ponzi (March 3, 1882–January 18, 1949) was an Italian immigrant to the United States who became one of the greatest swindlers in American history.

When Ponzi was released he eventually made his way back to Boston. There he met an Italian girl, Rose Gnecco, who was swept off her feet by Ponzi's charm. Though Ponzi did not tell Gnecco about his years in jail, his mother sent Gnecco a letter telling her of Ponzi's past. She remained with him nonetheless and they married in 1918. For the next few months he worked at a number of businesses, before hitting upon an idea to sell advertising in a large business listing to be sent to various businesses. Ponzi was unable to sell this idea to businesses, and his company failed soon after.

A few weeks later Ponzi received a letter in the mail from a company in Spain asking about the catalog. Inside the envelope was an international postal reply coupon (IRC), something which he had never seen before. He asked about it and found a weakness in the system which would in principle allow him to make money.

The purpose of the postal reply coupon was to allow someone in one country to send it to a correspondent in another country, who could use it to pay the postage of a reply. IRCs were priced at the cost of postage in the country of purchase, but could be exchanged for stamps to cover the cost of postage in the country where redeemed; if these values were different, there was a potential profit. Inflation after the First World War had much decreased the cost of postage in Italy expressed in U.S. dollars, so that an IRC could be bought cheaply in Italy and exchanged for U.S. stamps to a higher value. The process was: send money abroad; have IRCs purchased by agents; send the IRCs to the U.S.A.; redeem the IRCs for stamps to a higher value; sell the stamps. Ponzi claimed that the net profit on these transactions, after expenses and exchange rates, was in excess of 400%. This was a form of arbitrage, or profiting by buying an asset at a lower price in one market and immediately selling it in a market where the price is higher, which is not illegal.

Ponzi canvassed friends and associates to back his scheme, offering a 50% return on investment in 45 days. The great returns available from postal reply coupons, he explained to them, made such incredible profits easy. He started his own company, the Securities Exchange Company, to promote the scheme.

Some people invested, and were paid off as promised. The word spread, and investment came in at an ever-increasing rate. Ponzi hired agents and paid them generous commissions for every dollar they brought in. By February 1920, Ponzi's total take was US$5,000, a large sum for the time.

By March he had made $30,000. A frenzy was building, and Ponzi began to hire agents to take in money from all over New England and New Jersey. At that time investors were being paid impressive rates, encouraging yet others to invest.

By May 1920 he had made $420,000. He began depositing the money in the Hanover Trust Bank of Boston (a small Italian American bank on Hanover Street in the mostly Italian North End), in the hope that once his account was large enough he could impose his will on the bank or even be made its president; he did, in fact, buy a controlling interest in the bank. One biographer of Ponzi who wrote eighty years later described the cash price at which the bank's founding family sold their stake as suspiciously high. Having had a fiduciary duty to protect their depositors they were a lasting unindicted beneficiary without direct involvement.

By July 1920 he had made millions. People were mortgaging their homes and investing their life savings. Most did not take their profits, but reinvested.

Ponzi was bringing in cash at a fantastic rate, but the simplest financial analysis would have shown that the operation was running at a large loss. As long as money kept flowing in, existing investors could be paid with the new money, but colossal liabilities were accumulating.

Ponzi lived luxuriously: he bought a mansion in Lexington, Massachusetts with air conditioning and a heated swimming pool, and brought his mother from Italy in a first-class stateroom on an ocean liner. He was a hero among the Italian community, and was cheered wherever he went.